Titan Submersible Engineering Failure: What Went Wrong Beneath the Ocean

The Titan submersible engineering failure has become one of the most tragic and preventable disasters in modern deep-sea exploration. According to the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), OceanGate’s Titan imploded during its June 2023 expedition to the Titanic wreck site due to poor engineering decisions and a failure to conduct proper safety tests.

All five people aboard, including OceanGate’s CEO Stockton Rush, lost their lives instantly as the vessel collapsed under immense ocean pressure.

The official NTSB report revealed that Titan’s design, construction, and operation were riddled with errors that ignored standard marine safety protocols. Investigators concluded that the submersible failed to meet critical strength and durability requirements, making the catastrophe not just tragic, but avoidable.

How Poor Design Sparked the Titan Submersible Engineering Failure

Titan was a 6.7-meter (22-foot) carbon-fiber submersible reinforced with titanium domes. At first glance, it represented innovation. But experts later discovered that this same experimental design, praised for its light weight, was its downfall.

The NTSB stated the submersible had not been adequately tested to determine its real pressure limits. In other words, OceanGate didn’t truly know how much stress Titan could handle before it failed.

Engineers had also ignored early warning signs of material fatigue and delamination, meaning the craft was likely damaged before its final dive. Instead of retiring it, OceanGate continued to operate the vessel, a decision that sealed the fate of everyone on board.

A Journey to the Titanic That Turned Fatal

On June 18, 2023, Titan disappeared in the North Atlantic Ocean while descending toward the wreck of the Titanic, which rests approximately 3,800 meters below sea level, around 370 miles off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada.

Among the five aboard were:

-

Stockton Rush, OceanGate CEO and pilot

-

Paul-Henri Nargeolet, French deep-sea explorer

-

Hamish Harding, British billionaire

-

Shahzada Dawood and his 19-year-old son Suleman Dawood, both from Pakistan

Each passenger paid up to $250,000 for the expedition, described by OceanGate as a “mission of exploration.” But the NTSB found that the company’s approach blurred ethical and legal lines, calling paying customers “mission specialists” rather than passengers to evade safety regulations.

Titan Submersible Engineering Failure: Ignored Warnings and a Flawed Culture

During its investigation, the NTSB uncovered alarming details about OceanGate’s internal safety culture. While some employees claimed that safety was a top concern, others, including former marine directors and technicians, described a workplace where design flaws were ignored or dismissed.

One former technician told investigators he had warned CEO Stockton Rush about the company’s business model. He objected to selling seats to paying customers on an experimental vessel that hadn’t been certified by any regulatory body.

Under U.S. law, it is illegal to transport paying passengers in experimental submersibles. But instead of addressing these concerns, Rush allegedly replied that if the U.S. Coast Guard became a problem, “he would buy himself a congressman and make it go away.”

Such statements highlight a reckless disregard for oversight, one that directly contributed to the Titan submersible engineering failure.

Regulatory Gaps and Systemic Oversight Failures

The NTSB’s final report also criticized U.S. and international maritime safety standards, saying that current voluntary guidelines are insufficient to ensure accountability for experimental submersibles.

Because of these weak regulations, OceanGate was able to design, build, and operate Titan outside conventional classification standards, meaning no external safety body had approved its structural design or testing.

The board urged the U.S. Coast Guard to commission a study on pressure vessels that carry people and to update regulations based on its findings.

External marine experts, including researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, have echoed these concerns, emphasizing that proper testing and independent certification are essential for all future deep-sea exploration vehicles.

OceanGate’s Downfall: A Company That Ignored the Warnings

OceanGate has since shut down all operations. Its website, once promoting exclusive deep-sea adventures, now displays only a simple message acknowledging the tragedy.

Before the incident, OceanGate faced several warnings from the deep-sea engineering community. A 2018 letter signed by 38 ocean experts warned that Titan’s carbon-fiber design could “lead to catastrophic failure.” The company dismissed these warnings as “risk-averse.”

In hindsight, the experts were right. The Titan submersible engineering failure has become a global case study on what happens when innovation is prioritized over safety.

The Science Behind the Implosion

When Titan descended to a depth of 3,363 meters (11,033 feet), the hull experienced pressures over 4,800 pounds per square inch, more than 300 times that of surface air pressure.

Without sufficient structural integrity testing, the carbon-fiber shell buckled inward within milliseconds. The implosion was so fast that passengers likely died instantly, never realizing what happened.

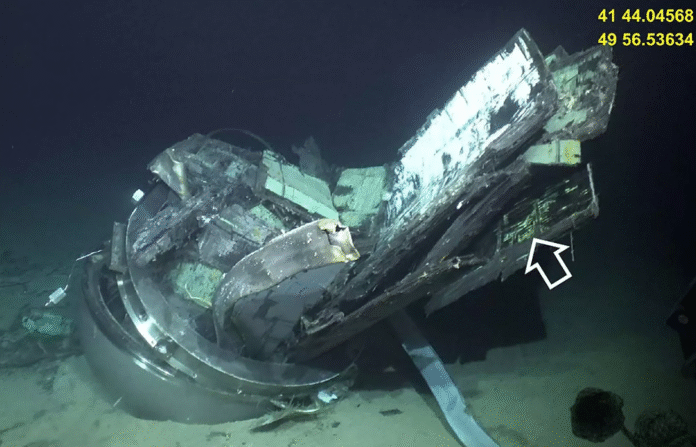

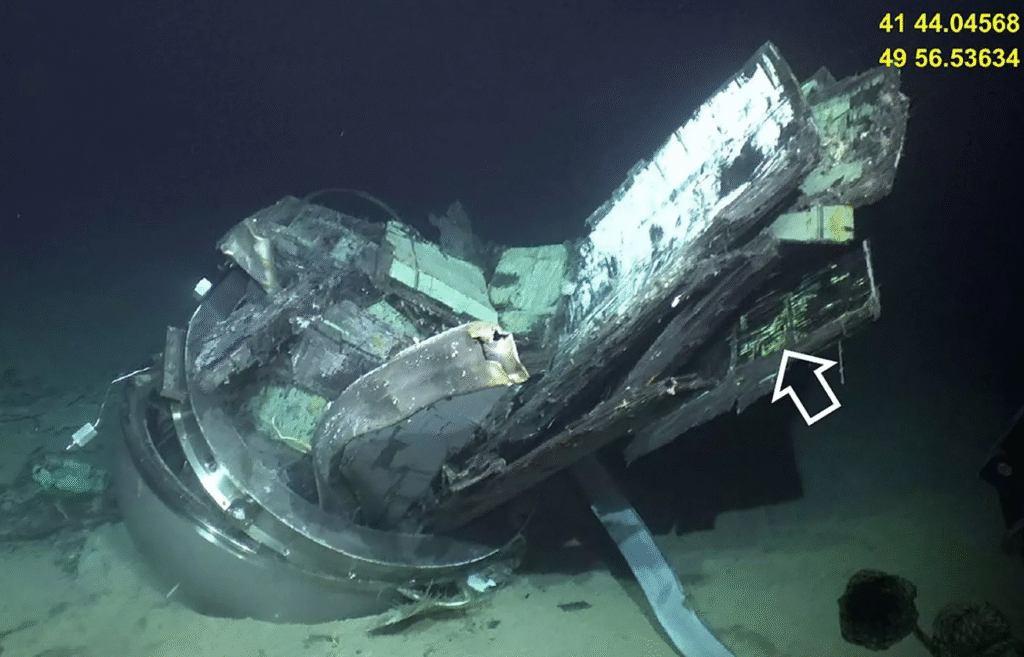

Footage released by recovery teams shows debris of the destroyed hull resting on the seabed, a haunting reminder of how human ambition can outpace engineering responsibility.

Titan Submersible Engineering Failure: Lessons for the Future

The tragedy has sparked global conversations about the ethics of exploration. Should companies be allowed to charge clients for rides in untested submersibles? Should innovation ever override safety standards?

Marine engineers agree that the Titan implosion has permanently changed how deep-sea expeditions are viewed. There’s now a renewed push for mandatory certification and transparency across the industry.

At the same time, families of the victims continue to call for accountability, hoping that stricter laws will prevent another Titan submersible engineering failure from happening again.

Conclusion: A Warning from the Depths

The Titan submersible engineering failure stands as a grim reminder of what happens when innovation outpaces accountability. The tragedy revealed not only the fragility of human technology under extreme pressure but also the urgent need for stronger safety regulations in deep-sea exploration.

As the world looks toward future ocean missions, one message is clear, progress without precaution can be deadly.