Recent Survey Findings

This summer, scientists found the Gulf’s low-oxygen area covers 4,402 square miles. That number sits 21 percent below the earlier June forecast of 5,574 square miles and 30 percent under last year’s 6,705 square miles count. This size marks the 15th smallest reading since tracking began almost four decades ago.

Field researchers from Louisiana State University and the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium took water samples by moving through nine spots off Louisiana and Texas from July 20 to July 25. They used sensors on a boat called Pelican to measure oxygen levels.

Why the Zone Matters

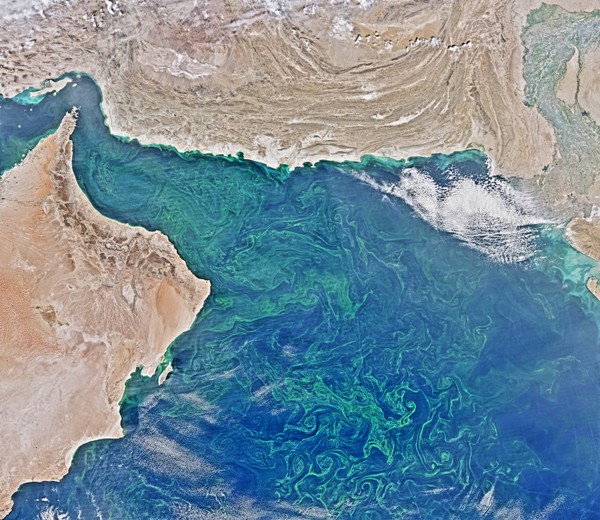

A low-oxygen area, often called a dead zone, can hurt fish and shellfish. When farms use heavy doses of fertilizer, rain carries those chemicals into rivers that run out to the Gulf. The extra nutrients make algae bloom. After the algae die, bacteria break them down and use up oxygen in the water.

Fish then leave or perish, and creatures such as clams and crabs cannot survive. This condition can cause catch rates to drop and push up costs for fishermen and seafood buyers.

Trend in Size Over Recent Years

Last year’s figure of 6,705 square miles ranked as the 12th largest dead zone ever recorded. Two years ago, in 2023, the zone spanned 8,185 square miles. In 2022, researchers measured 3,058 square miles. The five-year average now stands at about 4,755 square miles, still more than double the Environmental Protection Agency’s goal of cutting the area to under 1,900 square miles by 2035.

Expert Views and Personal Analysis

Laura Grimm, acting head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, called this drop an encouraging sign for coastal communities and marine life. I agree that the change shows promise. It suggests that joint steps by state agencies, farmers, and local groups can yield positive results. Yet the gulf still sees a large span of low-oxygen water.

Meeting long-term targets may require stronger rules and extra funding that one report values at roughly seven billion dollars per year for cleanup efforts. In my view, this level of spending could face political hurdles that delay wider action.

What Comes Next

Groups that track water quality plan to keep testing yearly. They aim to guide policy and farming practices along the Mississippi River watershed. Farmers may need to adopt buffer strips of plants next to waterways and curb fertilizer use at key times. Coastal towns could push for grants to improve sewage treatment and urban runoff capture. If these steps hold firm, the dead zone might shrink more in coming summers.

Sources: NOAA.com