Carbon Absorption by Land Nearly Stopped in 2024

Forests, grasslands, and wetlands have helped slow climate change for decades. These natural systems usually absorb around one-third of the carbon dioxide released by human activity. But in 2024, this process nearly came to a stop. New data shows that land-based ecosystems removed almost none of the carbon released into the air. This shift surprised scientists and raised fresh concerns about how fast climate systems are changing.

According to early data from satellites and atmosphere readings, the level of CO₂ in the air jumped by 3.73 parts per million in 2024. This was a bigger rise than what happened during the 2015–2016 El Niño event, which was already seen as a major climate warning.

Researchers expected some recovery after the severe fires of 2023. But what they saw instead was another setback—this time for different reasons.

What Changed in 2024?

In past years, even when drought or fires hit, land still managed to absorb a good amount of carbon. But in 2024, that changed. Tropical grasslands grew rapidly due to extra heat and rain. However, this extra growth led to more respiration, the process where plants and microbes release carbon.

Guanyu Dong from Nanjing University explained that the key driver in 2024 wasn’t fire, but ecosystem respiration. Heat speeds up chemical processes in plants and microbes, and moisture allows them to work longer. Together, they pushed out about 2.6 billion extra tons of CO₂—similar to what India produces in a year.

Why This Matters Now

Plants and microbes release carbon as they live and grow. When heat and moisture combine, this process becomes more intense. In 2024, satellite data showed that plants were greener than ever, but they also used more energy. That meant they burned more sugars and released more carbon.

Also, warm nights prevented normal cooling. In some areas, rivers flooded land, spreading plant matter and feeding microbes. These microbes released more CO₂ than usual. Though this process is invisible, its impact was larger than any fire that year.

Guido van der Werf from Wageningen University noted that even small changes in how fast microbes break down organic matter can change the whole picture. He said we need more on-the-ground data, especially from warmer parts of the world, to understand what’s happening underground.

Looking Back at Past Climate Events

Major El Niño events in the past cut into the land’s ability to absorb carbon. But those events mostly caused drought and fires. In 2024, fires burned less than they did in 2023. That makes this year’s carbon spike even more alarming. It suggests that fire prevention alone can’t solve the problem.

Researchers say the land’s ability to absorb carbon works on two switches: one for temperature, and one for rain. This year, global warming kept the temperature switch stuck in the danger zone, even though El Niño had faded.

One big takeaway is that tropical regions are now playing a bigger role in the global carbon cycle than forests in colder regions. Yet tropical grasslands get much less research attention or funding than rainforests.

What This Means for the Future

If the land no longer removes about 30 percent of emissions, then countries will have to reduce carbon emissions much faster. The 2024 total fossil fuel output was around 37.4 billion tons, slightly higher than 2023. But with the land doing little to help, it’s like burning much more.

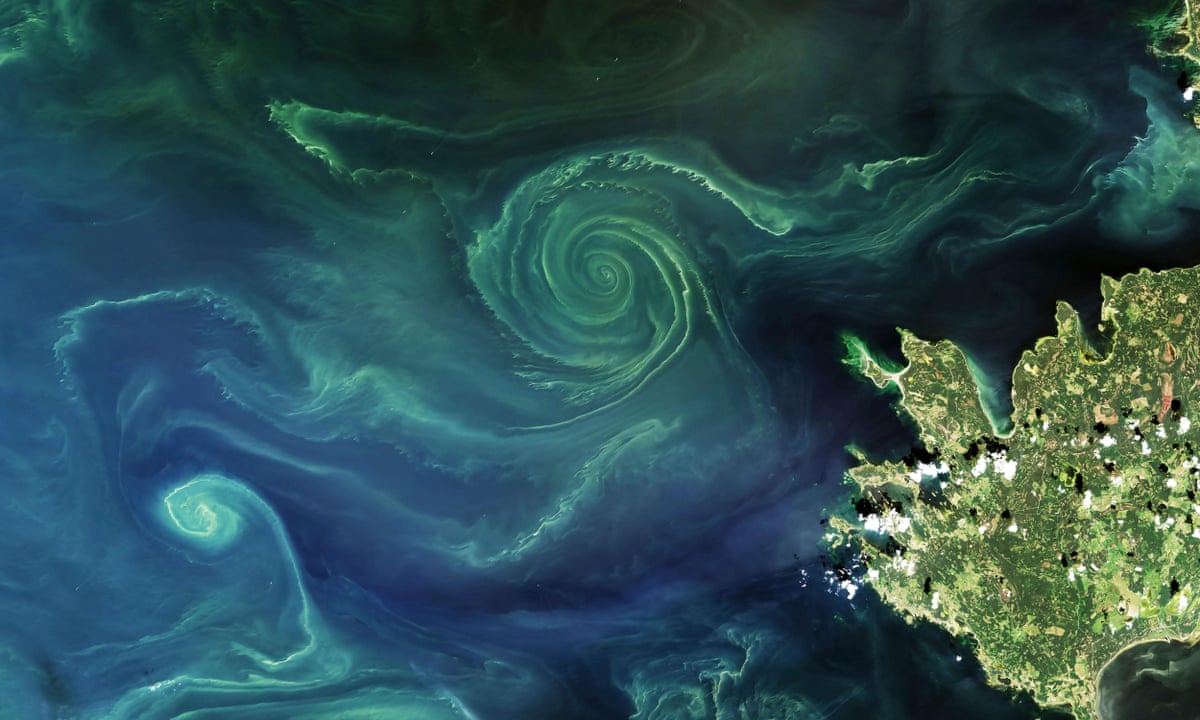

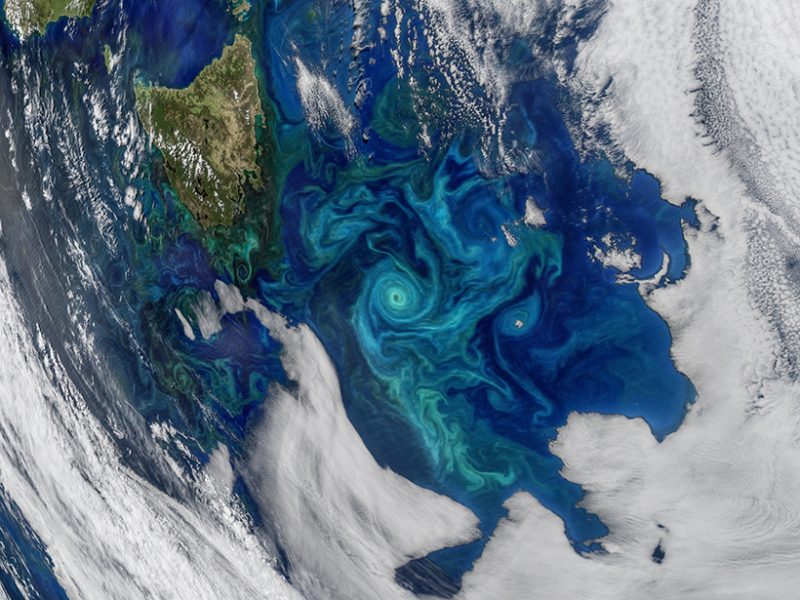

The oceans used to help by absorbing most of the heat. But warmer waters hold less carbon, and recent heat waves are putting stress on sea life like kelp and plankton, which also store carbon.

Some experts think we may need to lean more on technologies that pull carbon from the air. These include planting trees or machines that capture CO₂ directly. But these options are expensive and can’t fully replace the huge role natural systems used to play.

Final Thoughts

Scott Denning from Colorado State University said we should not rush to call this a full collapse. Two bad years can still be a random event. Some forecasts suggest that a cooler La Niña might arrive in 2025, which could slow down respiration and let plants catch up.

But there are still big gaps in what we measure. There are few tools in Africa and other key areas. Soil moisture, airborne CO₂, and more data from the ground would help scientists know if this is just a bump or something bigger.

Personally, I think the data from 2024 feels like more than a coincidence. It’s a wake-up call. Even if next year brings a slight rebound, we now know how close the system is to failing. We can’t keep counting on forests and grasslands to fix the problem on their own. That window is closing fast.

Sources: earth.com